On 9 December 2013, the Banadir regional court in Mogadishu sentenced a female journalist to house arrest as part of a six month suspended sentence on charges of “defamation and lying” after she claimed in an interview that she was raped by two government radio journalists.

The Radio Shabelle journalist who interviewed her–Mohamed Bashir Hashi–was found guilty on the same charges and paid a fine to avoid a six month prison sentence.

The court found Mohamed’s boss Abdimalik Yusuf Mohamud guilty of “offending Somali institutions and defaming Somali government officials,” and he also reportedly paid a fine rather than serve a 12 month stint in prison.

The alleged perpetrators were only briefly detained and had filed a defamation suit against the defendants. They evaded a sincere investigation into any potential wrongdoings.

Multiple Storylines

The case was mired in multiple storylines that obfuscated the real problem of violence against women in Somalia. As Somalia Newsroom noted before:

Radio Shabelle has been unafraid to post unflattering news about Somali politicians and militants with often deadly consequences.

The station’s journalists have said in the past they had been “ordered to report falsehoods” on the direction of the station’s owner…

Given the ramped up tension between Radio Shabelle and the SFG since the station was recently kicked out of its government-owned property, the media company has plenty of motivation to hit back.

As a result, Radio Shabelle’s ability to identify an alleged victim who accused two government-aligned journalists of rape is much more than just a curious footnote, and some media reports have failed to mention this key detail.

However, the woman’s claims should not be dismissed out of hand, and as many diplomats and rights groups have asserted, the allegations among all sides should be subject to a fair investigation with all sides entitled to legal representation and other freedoms.

Unfortunately, the government’s handling of the case reinforced its own challenges with the media and the law. The conclusion has not helped observers understand whether key details of the case were true or not. The process in which the defendants were prosecuted also raises legal questions.

Burden of Proof

By charging two of the defendants with defamation and lying, it put the burden of proof on the alleged rape victim and the journalist who interviewed her to prove that their claims were true—essentially creating a scenario in which they were “guilty until proven innocent.”

A similar reverse in the traditional burden of proof characterized the previous case in which journalist Abdiaziz Koronto and the alleged rape victim who he interviewed were convicted on charges of insulting the government and fabricating a story in the media; they eventually were released on appeal amid intense international pressure.

Both cases highlight the dilemmas inherent in a politicized judicial system that is struggling to reinstitute fundamental aspects of due process and justice.

In another case, bribes reportedly played a part in the early release of a man who murdered two Médecins Sans Frontières workers in December 2011. The convict was said to be living freely in the town of Guriel.

This injustice ultimately may have had significant humanitarian consequences in the country as MSF stated that this incident was a “final blow” contributing to its departure in August 2013.

In a case of arguably greater magnitude, veteran jihadi Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys continues his stay in legal purgatory following his flight from al-Shabaab infighting and negotiated surrender/arrest in June 2013.

Habar Gadir clan elders continue to pressure high-level government officials for the release of Aweys, who has not publicly denounced al-Shabaab or his own radical beliefs since being held in custody. The outcome could set an important precedent for future prominent al-Shabaab figures who want to defect or surrender to the SFG.

The government appears not to have reached a decision on whether to prosecute Aweys for his involvement with al-Shabaab or to allow him to live in a “gilded cage” in a foreign destination like Qatar–an option ostensibly complicated by a UN travel ban on Aweys.

More broadly, these cases show how identity, money, politics, and status often overcome simple application of the law in Somalia. But given the degree to which these factors influence legal systems throughout the world, the country’s challenges should not be looked at in a vacuum.

Two Promises

Only days before the Radio Shabelle case concluded, the UN and Somali government held its annual “open day” meeting on women, peace, and security.

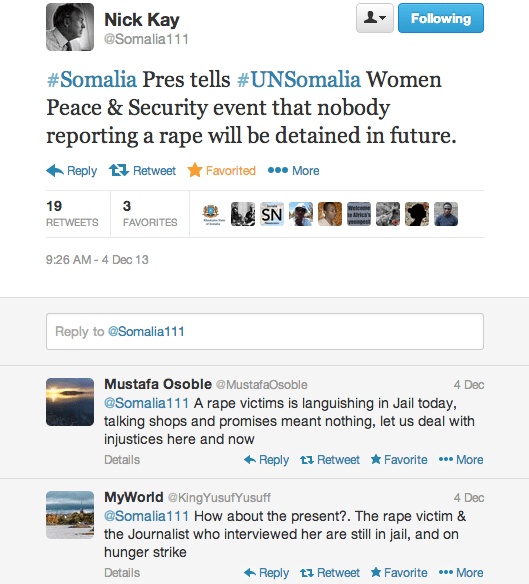

In a perplexing tweet about the event, UN Special Representative to Somalia Nicholas Kay repeated an interesting statement by Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud that no more women would be arrested because they report rape–which drew ire as another young woman was at that moment in jail for this reason.

Importantly, President Hassan’s administration emphasized in the Koronto and Radio Shabelle cases that the government would not “interfere” with the independence of the judiciary and security services during the course of their investigations.

So, President Hassan–intentionally or unintentionally–may have put the Somali government even further between a rock and a hard place on the occasion that another controversial rape case comes under the international spotlight.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Categories: Somali Government

Somali Government Announces New Election Timeline As Parliament’s Mandate Expires

Somali Government Announces New Election Timeline As Parliament’s Mandate Expires  Somali Government Continues Onslaught Against Domestic Rivals With Impunity

Somali Government Continues Onslaught Against Domestic Rivals With Impunity  Ways to Improve Somalia’s Plans to Take Over Security from Foreign Troops

Ways to Improve Somalia’s Plans to Take Over Security from Foreign Troops  Stunt or Stand for Democracy? Villa Somalia’s Response to the Failed Coup in Turkey

Stunt or Stand for Democracy? Villa Somalia’s Response to the Failed Coup in Turkey

Leave a comment